TOPOR Maria

Germany

‘Women are good at forming friendships,’ Quentin Bryce told a gathering at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, on 14 May 2015. ‘The friendship of women, their solidarity, is very important to their survival and growth as people.’ She was referring to the women of the Queensland CWA branch her mother belonged to and found much joy and fulfilment in.

But the former governor–general’s comments apply just as pertinently to the informal, unstructured group of migrant women who lived, worked and raised their children in the Benalla Migrant Centre. Unlike the CWA members, the majority of these migrant women were sole breadwinners. They had to work to support themselves and their children. They had few choices. With only functional English, no opportunities for further education or training, they were stuck in menial, low-paying jobs, either in the camp itself – in the mess hall kitchen – or in the Bush Nursing Hospital or chain or clothing factories. Apart from their immediate families, they had only each other for companionship and mutual support.

They knew they were disempowered. Whatever relatives they communicated with by letter were a long way away, in Europe. There was no extended family handy to consult or rely on. But there was Father Wosniczek, the Polish priest. It was he who arranged for Krystyna and me to attend St Joseph’s and later the FCJ Convent, on scholarship. Although I was separated from my friends at Benalla High School, I enjoyed the educational opportunities I received at the convent.

Educated women such as Mrs Zieds, literate in two or more languages, worked in a camp administration role, as translators and communicators of the Director’s instructions over the PA system. Her position valued good grooming and her salary enabled her to look smart and sound confident. She also had her own accommodation, near the school, separate from the rest of us. By comparison, the less well-educated women, assigned to unskilled work, seemed diffident and far less sophisticated.

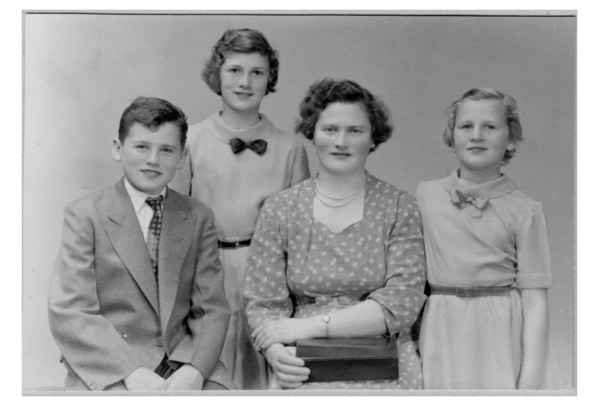

In 1957, when I was 10, my family left Scheyville Migrant Centre, near Richmond, NSW, to get away from our father, Kazimierz Topor. He had a history of violence. Benalla was our refuge. My brother, Ludwik, sister Krystyna and I were enrolled in the Aerodrome School on 12/12/1957 with, ironically, my father’s name on the school register, not my mother’s name, Maria Topor. It was our mother who took us to the school on our first day and our mother who was our primary carer. This was the first evidence I had of my mother’s invisibility in the eyes of camp authorities. She had no status in her own right. We hoped our father would never find us, but he did.

Communities are a two-edged sword. They can nurture and support, but they can also create dependency. Much depends on how much power communities have. The community of migrant women I knew during the late 1950s and mid 1960s were battlers in every sense of the word. When they came to Australia, many of them were already socially, economically and educationally disadvantaged, only to have those disadvantages compounded by what seemed like a one-way set of obligations and responsibilities under a patriarchal system.

Apart from occasional, usually prurient interest in our lives, no-one in the town seemed to care about us or our stories. Value lay firmly on our mothers’ economic contributions and their children’s indistinctness: nothing else seemed to matter.

For years, whenever I opened my mouth, people would immediately say, ‘You’re not Australian, are you?’ It wasn’t said unkindly, but our accents marked our Otherness. This had the effect of reinforcing our sense of identity as migrants. Instead of striving to be and sound like the townies, we prided ourselves on our differences. For example, I was shocked one Friday afternoon after school to hear Krystyna farewell one of her St Joseph’s classmates in broad Australian. It felt like a betrayal of some kind. She was born in Australia – affectionately dubbed a ‘kangaroo’ – by our family, so perhaps she felt she needed to blend in. In a nation fond of characterising people it comes as no surprise that some ethnic groups find their strength and identity in resisting pressure to blend into a national ‘blancmange’, and in maintaining their cultural distinctness with pride.

Living on the edge of Benalla, next to the airport, we were physically separate from the town – fringe dwellers of sorts, objects of occasional curiosity and sometimes scorn. Neither our mothers nor we, as children, were ever invited to anyone’s home in town. Only former migrants living in a Housing Commission houses would invite their friends to visit. The solidarity forged in the camp held across the ‘border’ that was Samaria Road and, later, across the suburbs of Melbourne.

I had only entered townspeople’s homes as a Girl Guide, gaining experience for my badges or doing odd jobs for senior citizens during Bob-A-Job week. With the power of books, films and television, our experience of how others lived was largely vicarious.

When my brother was 14, he and a town girl, Jill, had a crush on each other. They must have met at high school. She offered me her discarded tennis racquet which I collected from her large brick house in Coster Street. That was the first time I saw how a girl a year older than me lived. She had her very own, beautifully decorated bedroom, filled with possessions. A kookaburra sat in the stained glass round window that faced the street. By contrast, our few possessions fit into a small chest of drawers and a narrow wardrobe – standard Department of Immigration issue. Jill’s interest in my brother was short-lived and we never became friends, but I bashed a ball against the massive garage doors near the camp’s entrance until the warped racquet was no longer usable.

As children we were heir to our mothers’ lack of confidence and direction in life. We had no role models – except that of the battling single mother, tenacious and enduring. Although we were ‘feral’ – left to our own devices while our mothers worked – it’s surprising how few of us ‘turned out bad’. Our parents must have instilled in us core values of decency and acceptable behaviour which were, no doubt, reinforced by weekly attendance at Mass. In fact, we had a community of mothers admonishing and guiding us when our own mothers were at work.

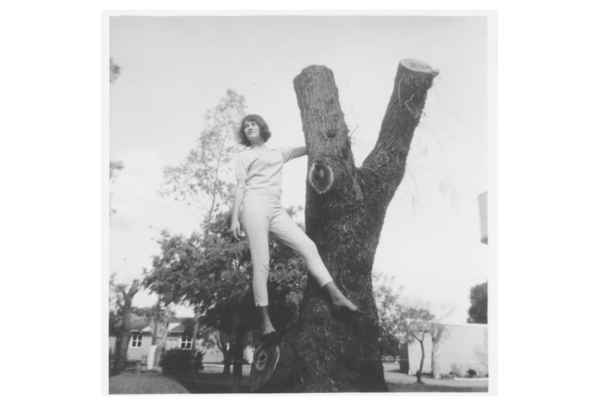

Outside the camp we were diffident and self-effacing. Within the safety of the camp, however, we played loudly and joyfully, unfettered among our own. We made up secret languages and wrote letters in invisible ink, knocked on doors and ran away, climbed trees, spied on people, especially young lovers – much to their annoyance – and played games such as Klipka. The idea was to place a 3-inch piece of wood whittled to a point on each end – the klipka – into the air with a plank from a fruit packing case and count the number of continuous airborne hits of the klipka. The winner was the one who could keep the klipka in the air longest. Well-formed klipkas were collectables.

While the adults idolised President John F. Kennedy, the children played Countries, a game that reflected the Cold War tensions of the time. A line would be drawn in the school playground dividing ‘the world’ into two teams, invariably America and Russia. Players would raid each other’s territories for items – usually stones, sticks or marbles – placed at the boundary of ‘the world’. The idea was to return to your own country with booty and without being tagged. If you were caught, you were a prisoner. Whichever country lost all its booty or all its people lost the game.

Marbles, knucklebones, Puszka (Kick the can), hide-and-seek, and cat’s cradle were other favourites, as were French knitting and handball. There was no end to the variety of games. With only low-tech items needed, everyone could play something. As we got older, games shifted indoors with the advent of board games such draughts, Snakes and Ladders, Ludo, Monopoly, and Chinese Checkers. Later again, listening to trannies, dancing rock’n roll and going to the movies marked our mid-teen years.

We prided ourselves on our physicality, dexterity, speed and strength, attributes soon recognised with alarm at Benalla High School. The ‘camp kids’ had to be separated at sports, otherwise we would have been invincible.

At the convent where I spent four years, the farmers’ daughters couldn’t understand how a kid like me with a funny name, strong accent and living in a tin hut in the camp, could top the class in English, term after term – and I wasn’t even Australian! No-one expected us to excel and, whenever we did, their sense of entitlement was challenged and made then uneasy. It seems not so different nowadays with the generally low expectations of marginalised people, including indigenous children, by the wider community.

Whatever abilities I had were recognised by others long before I did. For example, I wouldn’t have gone back to TAFE to complete my secondary schooling if it weren’t for the prompting of my boss – the third one I had trained. Promotions were not for young women, however promising, but for future breadwinners, that is, men.

It’s ironic that the traditional paradigm endured in my Sydney government department workplace years after I had left Benalla camp. The ‘big boss’ was an ex-Army Major and my immediate boss was an Anglo who, despite his struggles to successfully complete the HSC – his third attempt enabled him to study Economics at university – made an appointment for me to enrol at East Sydney Tech. He insisted I was ‘bright enough’ to pass first go, but I resisted for two years before enrolling. A whole new world opened up when I not only passed the HSC but also earned a Commonwealth University Scholarship.

A decade later, banks still wouldn’t grant me a home loan because I was a woman, despite the fact that I earned more money at the time than my husband. In fact, when I married my husband I was fortunate to have also ‘married’ his extended family. In the banks’ eyes, my value didn’t lie in my proven achievements and potential but in my association with my husband. The patriarchal paradigm raised more ire among women of my generation than it did before the feminist revolution. So what chance did our mothers have to move out of the camp when such inimical attitudes and practices prevailed, and still do in far too many quarters?

I longed for the day when I could change my name – no could pronounce it or spell it! I toyed with various Anglo names I could assume under deed poll. But when marriage presented me with the perfect opportunity to become Helen Stanley, I couldn’t do it. I hung onto Topor because that is who I am. It is a confirmation of my identity. My children carry the Topor name into their surname: Topor-Stanley.

Disempowered, disregarded and devalued, our mothers sought strength and comfort from each other and their growing offspring. Whatever dreams they had for themselves and their children were silent, unseen and unheard. By not leaving the camp earlier, they were judged as lacking initiative. Authorities saw all too clearly the psychological barriers for leaving, but they were blind to the structural inequalities that kept the women there far longer than was desirable for everyone concerned.

The stories of these women and their children must no longer remain hidden. They must be made public. The flourishing of their offspring is a testament to their parents’ frugality, hard work and endurance, as much as to their compassion for and solidarity with each other.

© Helen Topor

16 May 2015